Until recently, incense sticks were utilized in a special type of timepiece used exclusively in Japanese geisha houses (Okiya) to compute the cost of entertainment. The word geisha is a Sino-Japanese word meaning "a skilled person" and referred to girls in Japan who were professional singers and dancers. The word geisha is a compound the two characters which mean "art" and "person" respectively; another version of this is geinin. In the Osaka and Kyoto districts the word for geisha is geiko, a feminine diminutive suggesting that the public performer in those districts at this time was of only one sex, unlike the Yoshiwara geisha, where the word for "man," Otoko geisha, was attached to the name geisha.

Less known were the male geisha, or Hakoya, a product of the Yoshiwara who achieved professional recognition in 1778 with the establishment of the geisha registry office. Originally they had low social status and were classified as coolies. At first most of them were amateurs having other occupations who practiced entertainment in their spare time. Later, after they were absorbed in the registry office, they performed extraneous duties as messengers and general assistants. Subsequently they became known as Hokan, originally meaning "spare time helper." By the early nineteenth century, however, the male geisha achieved a much higher status, and several schools developed in which they were trained in music, poetry, flower arrangement and the tea ceremony. Lower ranked members of their profession remained primarily jesters but eventually, as the profession became more vulgarized, the male geisha was reduced to nothing more than a buffoon, and their number steadily dwindled.

The geisha came into existence in the mid nineteenth century, first on the eastern side of the Sumida River, in the purlieus of the shrine of the war god Hachiman in Fukagawa. Small boats from this quarter sailing up river were accustomed to mooring near a tributary of the Sumida and in time boat houses that had begun dotting the shores developed into tea houses which the Fukagawa geisha frequented. As a consequence it was not long before the outlet at Yanagibashi developed its own geisha community. In due course it became centered at Edo (later Tokyo). In time geisha were to be found where ever people gathered, and they particularly favored areas near public resorts.

The true geisha were required to undergo a period of strenuous training in singing and dancing, which sometimes began as early as at the age of seven. She was to be able to while away the time pleasantly for her guests. Accordingly, one requirement for a geisha was proficiency in music and possession of some knowledge of the samisen. She was to be able to sing and dance and discourse on the most trivial topics, and play such games as ken.

There were three types of geisha. The first was the jimae, who was her own mistress and lived in her own home. Another type was the kakae, who entered service in a geisha house under contract for a specified time period, and was supervised by a house mistress. Finally, there was the tateki-age, who was financially independent and associated herself with a geisha house because she may have lacked introduction to the tea houses in a locality in which she was a stranger. She was almost as free as a jimae but was required to earn enough to bring the house a fair profit. Then there were also the hangyoku, the geisha who were too young and had to be trained; they earned half as much as did the older ones.

There were two types of earnings for the geisha. There was the gyoku, the regular fee for entertainment that was added to the bill of the tea house to the guest. The fee was based upon time; in one of the better houses during a particular period the fee was twenty-five sen per hour.

Over the course of the years, the geisha was compensated by one of several systems. In the early period when a girl was apprenticed to a geisha house, the owner paid a fixed sum to the parents or guardian. For a stated period of apprenticeship, the novice received training, clothing and board and room at the cost of the mistress. After her training had been completed, her earnings were divided with the geisha mistress. The division often consisted of seven parts for the mistress and three for the geisha; by another system the earnings were divided half and half. It was possible also for a trained geisha to attached herself to a prominent geisha house, where she could live, paying all of her own expenses and arranging an independent system of sharing her earnings with the house mistress. In more recent times, geishas no longer were apprenticed; if a girl wished to become a geisha, when she reached the age of eighteen and had satisfactorily completed secondary school training, she could make application to a central registry office. She was interviewed before a selection board consisting of several senior geisha mistresses, during which she was required to demonstrate proficiency in one of the several arts noted. If accepted, she was registered and required to pay a monthly fee, during which she was expected to attend a school conducted by the central registry office. Throughout this period the girl lived at home and traveled to the geisha house in which she was registered.

A geisha’s fee was based upon the amount of time she spent entertaining a guest. The time was calculated on the basis of the burning duration of an incense stick, which was variously reported to be from twenty-five to thirty minutes. An entire evening was generally calculated to be equivalent to four incense sticks.

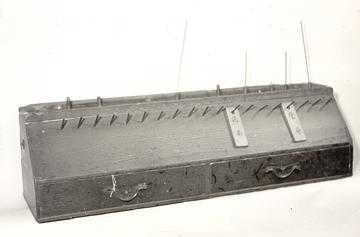

Incense sticks were stored in a senkodokei, a special box-like receptacle made of cryptomeria wood (sugi) having a flat or tented rectangular shape. Generally it measured about 8-1/2 inches in length, 4-3/4 inches in width, and 1-2/4 inches in height. The interior of the container was in the form of a drawer divided into two parts for the storage of incense sticks and holders. Twenty round holes were bored into the top of the container in two rows of ten in each row into which incense sticks held in bamboo holders were inserted. Each oiran or geisha of the establishment was assigned one of the openings, and it was customary to mark each one with a tag bearing the geisha’s name.

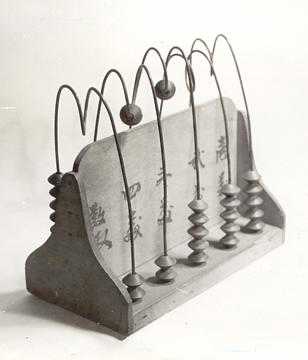

As each geisha became employed during the evening to provide entertainment for a visitor, an incense stick was attached to a bamboo holder, lighted, and dropped into the opening on top of the box opposite her name. When during the course of the evening the burning incense stick reached its end, it was removed and replaced with a fresh incense stick from the supply in the drawer, and the burned remnant was set aside with the geisha’s name. As the evening progressed, and the sticks had to be replenished, a soroban, a form of abacus, was used to compute the number of incense sticks consumed for each of the geishas.

According to Hyoe Takabayashi’s Tokei no hanashi, as late as 1924 geisha entertainment was being computed and charged on the basis of consumed incense sticks. Seven of these were expendable during the ten hours that made up the geisha working day. The charges for service were always listed on the bill as so much for so many "sticks."

The geisha timepiece was described in greater detail in a work by Ernst Junger, with details he had obtained from Giko [sic] Takabayashi. After describing the senkodokei, he went on,

Each time a girl retired with a guest, the host (or senior in charge of the geisha house) would light an incense stick and set it up for her . . . The duration of burning corresponded to a definite amount. A flower girl could say, "Yesterday I earned six sticks!" Today such boxes are no longer in use. But the Japanese word for the sticks, senko, still retains its meaning so that even today one asks what is the price in this or that district for a "flower girl incense stick." To such an elegance of the blossom language, we Western barbarians would never penetrate."

Related articles

Show moreSource

[Hyoe Takabayashi, Tokei no hanashi (Tokyo: Privately printed, 1924); Ernst Junger, Das Sanduhrbuch (Frankfurt am Mainz, Vittorio Klostermann, 1957), pp. 47-52; A. C. Scott, The Flower and Willow World (New York: Orion Press, 1980).]

For a comprehensive history of the use of incense for time measurement in Japan see THE TRAIL OF TIME. Time Measurement With Incense in East Asia by Silvio A. Bedini (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999)

https://books.google.com.vn/books/about/The_Trail_of_Time.html?id=xdVkzs6iI1YC&redir_esc=y

Copyright information:

Copyright 2002 -- Silvio A. Bedini

This article is published on Naturalscents.net with permission from Silvio A. Bedini - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silvio_Bedini